early origins

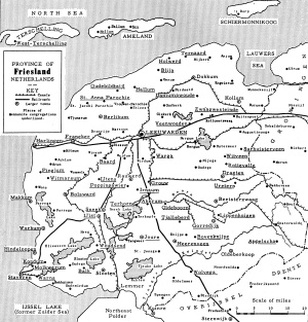

The area from which the Low German Mennonites originated is called “Dreier Friesland”. This is located in the Groningen and West Friesland areas, which then belonged to the Netherlands, and East Friesland, located in northern Germany. It was in these areas that a people who were known as the “Friesians” lived, many of whom later converted to the Mennonite faith.

In earlier times, the “Friesians” lived on the islands and coastal lands of the North Sea, before moving further inland. They were in constant battle with both the sea, which threatened to swallow their lands, and the Normans, their two greatest enemies. In the beginning of the eleventh century, the Friesians were conquered by the Normans. They had their land taken and many were sold as slaves. The Friesians were known as “Gottes Ehrenvolk” (God's honourable people) and the name itself is derived from a gothic word meaning “to be free”. Bartholomaeus Anglicus, a Franciscan Monk wrote that the Friesians were a strong, rough people, who were highly prideful of their freedom and unique ways. Roman documents describe them as courageous and loyal above all else. Friesian men declined being promoted to knighthood because they already saw themselves as knights. When Philip of Spain required the provinces of the Netherlands to pledge their oaths of allegiance, all bowed before him to swear fealty, save the Friesians, who declared “we kneel before God alone!”

The Friesians were a pagan people until the eighth century. They stood their ground against the Christian influences of the Franks for many decades, before a minority submitted to the teachings of Wilfrid, the bishop of York. Christianity was tolerated among the Friesians and slowly grew between 690 and 739 A.D. Only after 754, when the English missionary Boniface died among them as a martyr, was Christianity widely accepted among the Friesians. And so, out of these fiery Friesians, nearby Flemish tribes and other Anabaptists who relocated in Friesland when the persecution began during the Reformation, arose a people, known today as the Mennonites.

In earlier times, the “Friesians” lived on the islands and coastal lands of the North Sea, before moving further inland. They were in constant battle with both the sea, which threatened to swallow their lands, and the Normans, their two greatest enemies. In the beginning of the eleventh century, the Friesians were conquered by the Normans. They had their land taken and many were sold as slaves. The Friesians were known as “Gottes Ehrenvolk” (God's honourable people) and the name itself is derived from a gothic word meaning “to be free”. Bartholomaeus Anglicus, a Franciscan Monk wrote that the Friesians were a strong, rough people, who were highly prideful of their freedom and unique ways. Roman documents describe them as courageous and loyal above all else. Friesian men declined being promoted to knighthood because they already saw themselves as knights. When Philip of Spain required the provinces of the Netherlands to pledge their oaths of allegiance, all bowed before him to swear fealty, save the Friesians, who declared “we kneel before God alone!”

The Friesians were a pagan people until the eighth century. They stood their ground against the Christian influences of the Franks for many decades, before a minority submitted to the teachings of Wilfrid, the bishop of York. Christianity was tolerated among the Friesians and slowly grew between 690 and 739 A.D. Only after 754, when the English missionary Boniface died among them as a martyr, was Christianity widely accepted among the Friesians. And so, out of these fiery Friesians, nearby Flemish tribes and other Anabaptists who relocated in Friesland when the persecution began during the Reformation, arose a people, known today as the Mennonites.

The Reformation

Martin Luther’s 95 Theses lit fire to the Reformation in 1517, which brought about many changes in the sixteenth century. Despite all that Luther had learned in the Catholic state-supported church, upon studying the Bible for himself, he found that it was belief in Jesus Christ that would gain the masses entrance into heaven, rather than tithing or doing good works (which was what the church advocated at the time). This personal revelation was the heart of Luther’s religious movement. Although he encountered much opposition, Martin Luther gained an ever-increasing amount of supporters.

Once Luther broke the dam of Reformation wide open, many different Christian groups formed. A man named Andreas Karlstadt is considered the founder of one such group, the Anabaptists, which originated soon after Luther’s initial protests. Karlstadt was a friend of Martin Luther’s. He agreed with many of Luther’s theological ideas, but pleaded with him to place more emphasis on Christians imitating the life of Christ, and blending both good works and belief in Jesus. This fresh understanding of the New Testament brought three other revolutionary thinkers together: Conrad Grebel, Felix Manz and George Blaurock. One of the key concepts where they varied from other church theology, was that Christians were to be baptised upon their adult confession of faith, rather than as an innocent and ignorant child. This was the main difference between the Anabaptists and other groups that arose out of the Reformation, but it was enough to estrange them from many of the others.

Martin Luther’s 95 Theses lit fire to the Reformation in 1517, which brought about many changes in the sixteenth century. Despite all that Luther had learned in the Catholic state-supported church, upon studying the Bible for himself, he found that it was belief in Jesus Christ that would gain the masses entrance into heaven, rather than tithing or doing good works (which was what the church advocated at the time). This personal revelation was the heart of Luther’s religious movement. Although he encountered much opposition, Martin Luther gained an ever-increasing amount of supporters.

Once Luther broke the dam of Reformation wide open, many different Christian groups formed. A man named Andreas Karlstadt is considered the founder of one such group, the Anabaptists, which originated soon after Luther’s initial protests. Karlstadt was a friend of Martin Luther’s. He agreed with many of Luther’s theological ideas, but pleaded with him to place more emphasis on Christians imitating the life of Christ, and blending both good works and belief in Jesus. This fresh understanding of the New Testament brought three other revolutionary thinkers together: Conrad Grebel, Felix Manz and George Blaurock. One of the key concepts where they varied from other church theology, was that Christians were to be baptised upon their adult confession of faith, rather than as an innocent and ignorant child. This was the main difference between the Anabaptists and other groups that arose out of the Reformation, but it was enough to estrange them from many of the others.

Menno Simons

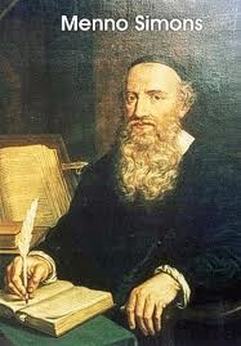

In 1536, a monk, turned Roman Catholic priest, from Witmarsum, West Friesland, came on the scene. Menno Simons, the son of a simple farmer, was convinced that the peaceful Anabaptist’s lives reflected true biblical standards. Simons was a well educated man for his times. He had learned Latin and Greek in Seminary and read many of the writings of early church fathers, but he was cautious of being led astray and so he avoided reading the Bible altogether. It was only after his second year as a priest that he opened the Bible for the first time. From the outside looking in, it appeared that Simons was all a priest should be. He led his congregation in Mass, prayed for both the living and the dead, baptised infants, officiated weddings, listened to confession, and so on. He was, however, questioning the very foundation he stood upon.

Simons’ critical points of doubt in regards to Catholic theology revolved around the rituals surrounding communion and infant baptism. He knew that the Anabaptists were persecuted for their adult baptisms, and yet he found no scripture supporting the state-church’s stance on infant baptism. He wrote to numerous church leaders concerning clarity in this matter, including Martin Luther, but upon hearing their responses, Simons felt that they were not scripturally grounded. Confused, he continued to study the teachings of the Bible. During about this time, a group of Anabaptists relocated into Simons’ home area, but although his beliefs were closely aligned to theirs, Simons kept his distance. After a time, Simons began preaching directly from the Bible. Stunned at the change in Menno Simons, the church leaders allowed this to go on for a few months before Simons himself decided to leave the Catholic church and resigned from his position in 1535. Thereafter, he was rebaptised by the Anabaptists. Menno Simons spent a full year in meditation and study of the Bible. Seeing his dedication, a group of Anabaptist men approached Simons requesting that he become their leader. Knowing the risks he was taking, he reluctantly agreed, and thereafter, the group became known as the Mennonites.

Because their newfound faith conflicted with some of the state-church’s theology, and a few Anabaptist groups, such as the Munsterites, who were not peaceful, they were all ruthlessly persecuted. Coming out of the Anabaptist movement, many Mennonites were also arrested and killed as martyrs. In 1540, Anna von Oldenburg, became duchess of East Friesland, Germany, and allowed her territory to be a refuge for any Anabaptist refugees. Among them was Menno Simons. He remained there only a couple of months before relocating in Cologne, and later to Holstein where he died a natural death in 1561. The majority of Menno Simons’ convictions and perceptions of the Bible were way before his time, but are mostly a part of common Protestant theology today.

In 1536, a monk, turned Roman Catholic priest, from Witmarsum, West Friesland, came on the scene. Menno Simons, the son of a simple farmer, was convinced that the peaceful Anabaptist’s lives reflected true biblical standards. Simons was a well educated man for his times. He had learned Latin and Greek in Seminary and read many of the writings of early church fathers, but he was cautious of being led astray and so he avoided reading the Bible altogether. It was only after his second year as a priest that he opened the Bible for the first time. From the outside looking in, it appeared that Simons was all a priest should be. He led his congregation in Mass, prayed for both the living and the dead, baptised infants, officiated weddings, listened to confession, and so on. He was, however, questioning the very foundation he stood upon.

Simons’ critical points of doubt in regards to Catholic theology revolved around the rituals surrounding communion and infant baptism. He knew that the Anabaptists were persecuted for their adult baptisms, and yet he found no scripture supporting the state-church’s stance on infant baptism. He wrote to numerous church leaders concerning clarity in this matter, including Martin Luther, but upon hearing their responses, Simons felt that they were not scripturally grounded. Confused, he continued to study the teachings of the Bible. During about this time, a group of Anabaptists relocated into Simons’ home area, but although his beliefs were closely aligned to theirs, Simons kept his distance. After a time, Simons began preaching directly from the Bible. Stunned at the change in Menno Simons, the church leaders allowed this to go on for a few months before Simons himself decided to leave the Catholic church and resigned from his position in 1535. Thereafter, he was rebaptised by the Anabaptists. Menno Simons spent a full year in meditation and study of the Bible. Seeing his dedication, a group of Anabaptist men approached Simons requesting that he become their leader. Knowing the risks he was taking, he reluctantly agreed, and thereafter, the group became known as the Mennonites.

Because their newfound faith conflicted with some of the state-church’s theology, and a few Anabaptist groups, such as the Munsterites, who were not peaceful, they were all ruthlessly persecuted. Coming out of the Anabaptist movement, many Mennonites were also arrested and killed as martyrs. In 1540, Anna von Oldenburg, became duchess of East Friesland, Germany, and allowed her territory to be a refuge for any Anabaptist refugees. Among them was Menno Simons. He remained there only a couple of months before relocating in Cologne, and later to Holstein where he died a natural death in 1561. The majority of Menno Simons’ convictions and perceptions of the Bible were way before his time, but are mostly a part of common Protestant theology today.

Resources:

Reuben Epp, The Story of Low German & Plautdietsch (Hillsboro, KS: The Reader's Press, 1993), 6, 49, 50, 51.

Cornelius J. Dyck, An Introduction to Mennonite History (Scottdale, Pennsylvania: Herald Press, 1993), 29, 30.

Anna Brons, Ursprung, Entwickelung und Schicksale der Taufgesinnten oder Mennoniten (Norden: Diedr. Soltau), 24.

Harold S. Bender, Menno Simons' Life and Writings (Scottdale, PA: Mennonite Publishing House, 1936), 1, 2, 15-30, 51, 52.

E. H. Broadbent, The Pilgrim Church (Grandrapids, MI: Gospel Folio Press, 1999), 200, 201.

Photos retrieved from:

http://gameo.org/index.php?title=Friesland_(Netherlands)

http://www.biography.com/people/martin-luther-9389283

http://www.mennoniteheritagetours.eu/

Reuben Epp, The Story of Low German & Plautdietsch (Hillsboro, KS: The Reader's Press, 1993), 6, 49, 50, 51.

Cornelius J. Dyck, An Introduction to Mennonite History (Scottdale, Pennsylvania: Herald Press, 1993), 29, 30.

Anna Brons, Ursprung, Entwickelung und Schicksale der Taufgesinnten oder Mennoniten (Norden: Diedr. Soltau), 24.

Harold S. Bender, Menno Simons' Life and Writings (Scottdale, PA: Mennonite Publishing House, 1936), 1, 2, 15-30, 51, 52.

E. H. Broadbent, The Pilgrim Church (Grandrapids, MI: Gospel Folio Press, 1999), 200, 201.

Photos retrieved from:

http://gameo.org/index.php?title=Friesland_(Netherlands)

http://www.biography.com/people/martin-luther-9389283

http://www.mennoniteheritagetours.eu/